Make Britain Great Again Invades Communist Bookstore

Information technology's impossible to say exactly when the rehabilitation of Patrick Buchanan began, partly considering his banishment from polite company was never total. MSNBC rather publicly fired him in 2012—over the protests of Joe Scarborough and Mika Brzezinski—after the publication of Suicide of a Superpower, the latest, though by no means the shrillest, in the series of duck-and-cover, they're-coming-for-usa screeds he's been writing since 1998. With chapter titles like "The Expiry of Christian America," "The End of White America," and "The White Party," it sounded the alarm of demographic apocalypse, offering pungent observations such as: "U. S.-born Hispanics are far more probable to smoke, drink, abuse drugs, and go obese than foreign-born Hispanics."

And yet two years later, there he was once more on Forenoon Joe, serenaded with the Welcome Dorsum, Kotter theme song. On camera, Buchanan plugged his new book, The Greatest Comeback, which tells how he helped Nixon become elected president, a iii-year siege that raised a repeat loser from the dead. Buchanan is a vivid storyteller, and his account draws amply on his personal archive of briefing papers, letters, and notes. The book also illuminates the Nixon years' atmosphere of cultural embattlement, a political mood that looks more relevant than ever in the Age of Donald Trump.

So do Buchanan's three long-shot attempts, in 1992, 1996, and 2000, to become president himself. He never came close to winning, but each fourth dimension he nagged at something, rubbed a nerve in but enough voters of a detail kind—what he called "peasants" and we phone call the white working course—to transport ripples of panic through the Republican party. The echoes of Buchananism in Trump's campaign were a pet theme during the election and its aftermath. But if annihilation, the debt has been understated. Put about simply, Buchanan begat Trumpism as his former ally William F. Buckley Jr. begat Reaganism. The also-ran of the Republican hard Right is the intellectual godfather of our current revolution.

It's true that Trump constitute his own mode, as early on as 1987, to the America Outset platform he ran on nearly thirty years afterwards. Only it was Buchanan who sounded, or brayed, the message nosotros all at present know by heart: anti-immigrant, anti-Europe, anti-Asia, anti-gratis-merchandise, anti more or less anything that inches America abroad from the splendors of the 1950s.

It's a curious fact of Buchanan's political history that his crusades are remembered as other men's defeats—George H. W. Bush's in 1992 and Bob Dole'south in 1996. Both secured the Republican nomination, merely simply after Buchanan beat them up and exposed them as out-of-touch frontmen for the GOP elite. In '92, amid a slumping economy, Buchanan railed against Japan'south "predatory trade policies" and an agreement with Mexico later called NAFTA. The Usa, he suggested, should call up about quitting the World Banking concern and the International Budgetary Fund. These heresies got him 37.5 percent of the vote in New Hampshire confronting the drinking glass-jawed incumbent Bush. Four years later, declaring himself the tribune of "a conservativism that gives voice to the voiceless," Buchanan won the country outright, beating Dole by a percentage indicate. Dole recovered in afterward primaries, merely, like Bush-league, he staggered on rubbery legs to the terminate line, where Bill Clinton was waiting.

Trump too belongs to the company of the Buchanan-scarred. The confrontation happened in 2000, when Buchanan, having get a pariah within the GOP, made a quixotic last stand on the Reform party ticket. Trump, even more quixotically, sought the Reform nomination, too, swaggering in with a book to promote and gasbag talk of the $100 million he would spend to get on the ticket and then to win "the whole megillah." Before Buchanan smacked him down, Trump got in some preemptive sore-loser licks. "Look, he's a Hitler lover," he said. "I guess he'south an anti-Semite. He doesn't similar the blacks, he doesn't similar the gays." For in one case affecting a statesman's high detachment, Buchanan said simply that the Reform political party and the presidency weren't for sale.

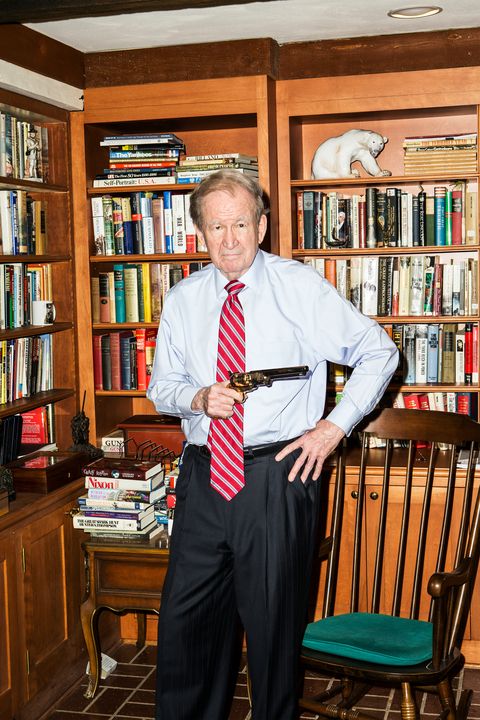

He remembers information technology all today, as he remembers much else in his half-century of national politics, equally a quasi-joke. "Somebody said, 'Pat, he called yous a Nazi, a Hitlerite.' I said, 'With Trump, you lot have to realize, these are terms of endearment.' " Sitting in the living room of his big Georgian house in McLean, Virginia, just later the inauguration, Buchanan lets out a soft roar, his optics disappearing into his still-meaty confront. He turned seventy-viii in November, and the thousands of hours on the road, the layers of TV pancake, have wrinkled his pug features, while his hair has faded toward apricot and is thinning in dorsum. Merely his laughter is alive and happy. And why not? He did in 2000 what sixteen Republicans couldn't do in 2016, despite the best efforts of William Kristol, the halfhearted pushback of the Koch brothers, and the whole machinery of "Conservatism, Inc." Not but that: The platform from which Buchanan once exuberantly ranted is now GOP doctrine and is fast becoming the law—or the multiplying illegalities—of the country.

Buchanan grew up in a behemothic family unit in northwest Washington, D. C., ane of nine kids. He and three brothers, born in successive years, formed a posse of brawlers and street fighters, "the scourge of Washington's Cosmic customs," according to Maureen Dowd, who grew upwardly hearing tales of "the latest Buchanan hooliganism." Buchanan has written about it, too, with undisguised nostalgia, in his autobiography, Right from the Beginning. He is not a human for 2d thoughts, whether about the sucker punches he threw and captivated or the cold-state of war religion he learned in parochial schools and at home. His father was a prosperous accountant who burned incense to the homegrown anti-communist martyrs Joe McCarthy and General Douglas MacArthur, and to the afar savior Generalissimo Franco. In Right from the Kickoff, Buchanan fondly recalls how he and his schoolmates at Blessed Sacrament flung snowballs at the "Boston Blackie," a bus that carried black cleaning women out to the leafy white suburbs, in 1950. Near 70 years subsequently, the man who disparaged Barack Obama'southward historic speech well-nigh the Reverend Jeremiah Wright and the politics of race as"the same old con, the same old shakedown" may be no one's ideal of a prophet or wise man, but he has quite maybe get, to quote David Brooks, "the most influential public intellectual in America today."

Requite Buchanan points for consistency, at to the lowest degree, and for self-effacement, conditioned past years as a backroom White House aide. "I heard from Trump during the primaries," he says. "He chosen about columns of mine that he liked. Just I did non hear from him in the fall ballot. And I've not talked to him since. I was delighted when he got in."

In fact, Buchanan has been plugging Trump for months in the column he writes on Mondays and Thursdays for his website. Trump has his share of defenders—including a handful of intellectuals—just it's prophylactic to say that only Buchanan would defend the president's directive almost transgender access to bathrooms by citing Rerum Novarum, Pope Leo Xiii's 1891 encyclical.

"How can such a fanatic be so likable?" Garry Wills, a Buchanan watcher since the 1968 campaign, has wondered. Wills, no pushover, isn't solitary. Michael Kinsley has Buchananitis. George Packer has it, too. "Pat Buchanan is a nativist, an isolationist, and an armed-to-the-teeth culture warrior," he wrote in 2008, afterward interviewing Buchanan in McLean. "He's also a very nice man and a wonderful raconteur."

There is no deep mystery to Buchanan'south talent for disarming writers. He's one of them—a lover of skilful prose and poetry, an observer with peeled eyes and keen ears, a pack-rat archivist of his ain career whose voice and mind hum with bold ideas and clever arguments. And he'southward i of the premier phrasemakers in mod American politics. Connoisseurs take their favorite entrada lines. Mine both come up from 1996: The offset was his mockery of Dole and the GOP regulars as "the bland leading the banal"; the 2d came afterward Buchanan got trounced in viii primaries on a unmarried Tuesday and shouted, with a cackle, "We are going to fight until hell freezes over, and then we're going to fight on the ice."

The other thing writers like, and envy, is where Buchanan's verbal gifts take taken him: into the thick of the political scrum. He has stumped through dozens of primaries, absorbed a national political convention (in Houston, in 1992), and spent hours giving advice to peachy men who actually read what he wrote and listened to what he said.

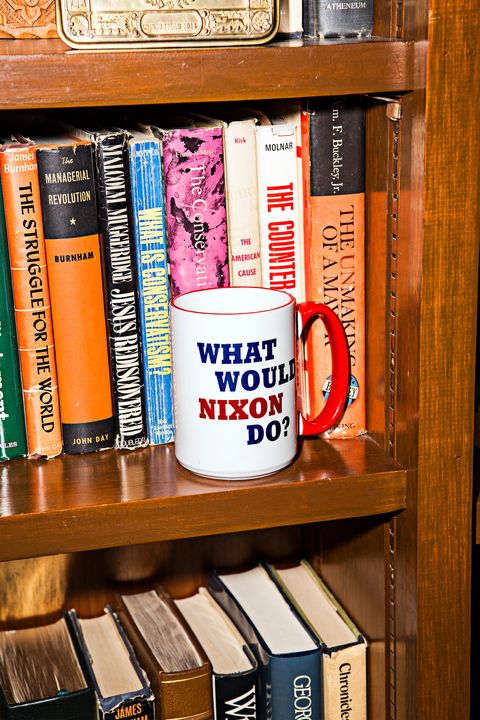

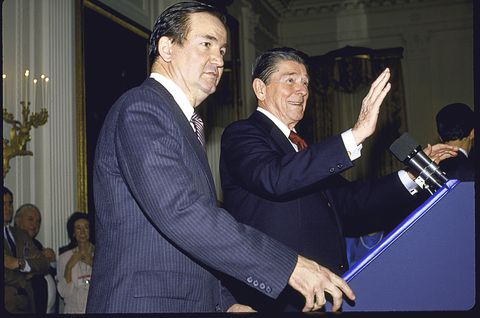

Buchanan met his wife, Shelley, when they worked together on Nixon's staff. Their pillared white house in McLean, next door to the CIA compound, is a homey museum of Buchanan's career, with artifacts on open brandish: vintage replicas of pistols endemic by his military heroes; a glass-fronted case with a pitchfork, souvenir of the 1996 entrada; and, in an alcove, photographs of Buchanan huddling in the White Business firm with the iii presidents he served—Nixon, Ford, and Reagan.

It was in this living room that correct-wing zealots gathered in January 1987 to anoint Buchanan their new leader, God's honest heir to Goldwater and Reagan. "Let the bloodbath begin!" 1 of them shouted. Buchanan loves the sanguine talk, only his ain idiom is quite oftentimes refined, even bookish. Just a homo besotted with words, who has a feel for historical irony, could begin his testimony before the Senate Watergate Committee by maxim, "You're looking at the Buckminster Fuller of dingy tricks." It was a bravura operation, and left Nixon airheaded with the conventionalities that Buchanan had dealt a "decease blow" to the committee. He hadn't, of course. Just his quick-jab sparring with inquisitors like Senator Sam Ervin fabricated Buchanan a star, and gave even the Nixon haters a villain they could enjoy, if non root for.

Buchanan revisits much of this history in his new book, Nixon'due south White House Wars, his thirteenth and perhaps best timed. The wars he describes, in opulent detail, were waged against the media, much similar the 1 we're seeing at present. Barely thirty, Buchanan was Nixon's Stephen Bannon, the in-house ideologue and commando-in-principal who goaded Nixon into taking on "big media"— especially the TV networks, The New York Times, and The Washington Post—and so wrote the scripts for the attacks.

Buchanan likes journalists as much as they like him. He used to exist one, and was good at it. A scholarship pupil at the Columbia School of Journalism, he was tutored by moonlighting Times editors and and then got on the fast rail at the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, a bastion of Midwest conservatism. His long postmortem on the trouncing of his early hero, Barry Goldwater, in the 1964 election was tough-minded and just. "The senator was vague, his analyses also simple, his proposals shallow," Buchanan wrote, at age 20-five. But, he added, the revolution was only beginning, and was bigger than the human being who had led it. "The new conservatism antedated Goldwater, made him a national effigy to rival Presidents, and volition post-date him," Buchanan predicted. "In that location is no sign the conservative motion will wither and die. It has lost the boxing, not the war."

Fourteen months later, Buchanan quit the World-Democrat and joined Nixon's staff, with a big salary hike, from $9,000 to $13,500 (a footling more than $100,000 today). The two had a history going back to the fifties, when Nixon was the vice-president and Buchanan was earning pocket money at the Called-for Tree golf gild. Assigned in one case to caddie for Nixon, Buchanan followed him into the bushes and unzipped side by side to him, against club rules. If Nixon minded, he didn't say so.

Joining Nixon's staff, in 1965, Buchanan knew exactly what his job was: to mend fences with the hardcore Correct, including the ideologues at National Review. For them, Nixon had been the errand boy of Dwight Eisenhower, the moderate they despised for governing from the center and failing to scroll back the New Bargain.

Out in the state it looked different. Eisenhower was the hero of World State of war II who so got us out of Korea and kept us out of Armageddon with the Soviets. Nixon was his inferior partner, the respectful not-com who had waited his plow.

Buchanan thrilled to something else—Nixon the difficult-edged political fighter and GOP loyalist. Together they toured the land in accelerate of the crucial 1966 midterms, tirelessly helping candidates for the House and Senate, edifice up goodwill. Those surprised at Buchanan'south own balletic presidential campaigns, done on a shoestring, forgot his apprenticeship with Nixon, the pioneer technician of modern retail politics.

Nixon won in 1968, but simply barely. He got only 43 pct of the vote and failed to carry either the House or the Senate, no thanks to George Wallace, the Alabama fire-breather, who won 13 percent and 5 states in the Balloter College—all defecting Democrats, but now Republicans in the making, if the party would fine-tune its message. The state was splitting at the seams over Vietnam and civil rights. The game, or war, was virtually "the sixties": the protests, the culture disharmonism, the polarization.

In 1968, the political experts were all looking in the wrong place, just every bit they would do in 2016. "The young, the antiwar groups, the mass demonstrations," Buchanan remembers. But Nixon's men picked up a different indicate: The eye was beingness ignored and was there for the grabbing. "You could carve off the conservative wing of the Democratic party, populist and conservative—Northern Catholics and Southern Protestants we called them and so—and bring them into the Republican party of Goldwater and Nixon." A few liberal Republicans would flee, but the GOP would "wind up with the larger half of the country." Out of this came Nixon'due south 1972 landslide, on a calibration unthinkable today: 60 pct of the vote, forty-nine states.

To hear Buchanan sift through this, with his easy command of electoral numbers and voting trends, is to experience how thin and hollow our politics has become. "Northern Catholics" and "Southern Protestants" still exist in America, merely you wouldn't know it. They take been crowded into an undifferentiated mistiness—white and Christian, with no shadings. Merely Nixon's men grew up in a denser geography of ethnic difference, full of prickles and thorns. They used terms like "lower-center-class Irish gaelic Cosmic": Daniel Patrick Moynihan'southward description of Buchanan, in a letter of the alphabet sent when both were working for Nixon. The two were ideological foes but, when it came to elites, of one suspicious mind.

Subsequently accounts would bandage all this as a politics of biting polarization, the marshaling of resentments and grievances. And indeed it was, to a considerable extent—"the whole secret of politics—knowing who hates who," as Kevin Phillips, a lawyer and the master strategist of Nixon's new majority, summarized information technology at the time. Phillips was a prodigy who at fifteen had begun working out the intricacies of shifting voter allegiances going back to the nineteenth century. Even younger than Buchanan, he had gone on to work for Nixon'southward 1968 campaign and in his administration. His 1969 book, The Emerging Republican Majority, elevated voter analysis into a rarefied fine art. "American voting patterns are a kaleidoscope of sociology, history, geography and economic science," Phillips wrote. "The threads are very tangled and complex, only they tin exist pulled apart." Phillips unknotted those threads in formulations similar this: "The sharpest Democratic losses of the 1960–68 menstruation came among the Mormons and Southern-leaning traditional Democrats of the Interior Plateau."

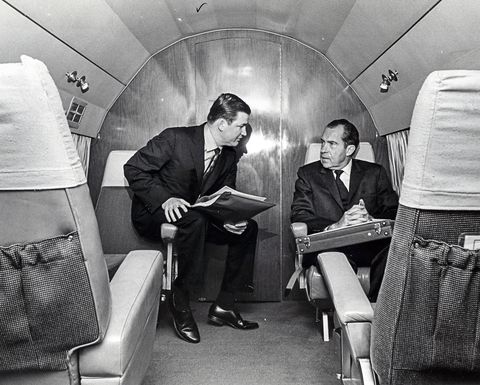

Phillips and Buchanan both became famous thanks to Garry Wills's Nixon Agonistes, the corking chronicle of the 1968 presidential campaign. Nixon'due south "fresh batch of intellectuals" included Phillips, with his color-coded charts, "a dumbo little mosaic of colors and figures that seemed to divide the land non into states or counties, but almost past street"; and Buchanan, in his blackness overcoat, "with the neckband wrapped upwards around his lumpy raw face," his "briefing file on all current affairs," and the fluent press statements he wrote for Nixon while reading up on the 1960 election in Theodore White's The Making of the President.

The portrait—which Buchanan at one time could summon from retention—was a advantage from Wills, National Review'due south virtually gifted writer. Buchanan had gotten him face-fourth dimension with Nixon after Buckley, the mag'southward editor, and William Rusher, its publisher, came around on the candidate. "Rusher calls me," Buchanan remembers, "and says, 'We're doing a big National Review takeout on Nixon. Garry Wills is gonna practice it. And you gotta bring him in to see all the Nixon people.' I said, 'Bill, I can't do information technology. We're about to head into New Hampshire. I tin can't requite this guy all that time just for an commodity in National Review.' He implored and begged me, and Wills came in and talked to everybody. Then nosotros got him time on the plane with Nixon." The interview, one of the most memorable in Nixon Agonistes, was first published not in National Review but in this magazine. (Wills, for his part, says the commodity had been deputed past Esquire from the beginning.)

For Wills, "Nixon's master problem, I think, was his nose," Buchanan recalls. He's serious. Nixon's ski-jump nose, beloved by caricaturists, was a staple of the catamenia's nostalgic humor. Even Nixon worked upward good-sport one-liners. ("Bob Hope and I would make a great ad for Dominicus Valley.") Wills, crammed beside him in a DC-3, nether the dim overhead spotlight, was transfixed—non by the nose'southward fabled length just past "its pitiful width, accentuated by the depth of the ravine running down its heart, and by its full general fuzziness . . . the olfactory organ swings far out; then, underneath, it does non rejoin his face in a straight line, but curves far upward again, leaving a large only partially screened space between nose and lip," etc. On it went, Cyrano de Bergerac by way of the New Journalism.

Nixon was appalled. For two years he'd been trying to shed the loser'southward prototype that haunted him after ii election flops (for president in 1960 and governor of California in 1962), and here he was getting "kicked around" over again—for his nose!—by a virtual nobody. Nixon never got over it, Buchanan says, withal amazed and shaking with hilarity. "All during the entrada: 'Remember, you brought him in, Buchanan.' Near his expiry, he reminded me, 'You were responsible!' " A wild hoot of laughter. "He would not allow me forget it!"

It was Buchanan'southward job to find a metaphor for Nixon's "new majority," which was useful shorthand for politicos talking shop just not for a public that needed poetry. A phrase had come to Buchanan during the rut of the 1968 campaign. With Nixon safely nominated in Miami, Buchanan and others went to the Democratic convention in Chicago. They stayed at the Hilton, on the nineteenth floor. "We had a suite," Buchanan says, "and were invitin' the journalists up. Norman Mailer walks in with José Torres, the boxer."

Mailer, who would depict the conventions in Miami and the Siege of Chicago, another of the period's bully political books, was exactly Buchanan's type: a writer with a muscular prose style who also used his fists. The two hit it off easily. "We're drinkin' and talkin'. We hear this mayhem exterior. We went to the window." On the streets below, the constabulary were advancing on some ten yard demonstrators in Grant Park. "The cops were in a phalanx, all marching like they were in the inaugural parade, but not as many. And they came right downwards Balbo, beyond Michigan, right in front end of our hotel. And these guys"—the police—"poured into that park and they were whalin' on these people left and right."

A federal commission would subsequently conclude that the cops in Chicago had rioted. Simply Buchanan was on their side, and he was confident the new majority was, too. He sent a memo to Nixon urging him to visit Chicago and "stand up with the dandy silent majority against the demonstrators."

In that location it was: "silent majority," a variation on the Depression-era "forgotten man," with an important difference. The forgotten man, who would return in Trump's inaugural address, was downtrodden, haunted, and hurting, a step away from the poorhouse. The silent bulk were his more fortunate but equally anxious offspring, belongings on to what they had in America's flush postwar society even every bit ceremonious-rights protesters, antiwar radicals, left-wing professors, and Ivy League journalists all conspired to take it away or ship it upwardly in flames.

The phrase had gone into one of Nixon'due south key speeches, given in November 1969 at the height of the antiwar protests and carried past all three major networks. "And so tonight," Nixon said, after outlining a strategy for getting out of the war by turning it over to the South Vietnamese, "to you, the neat silent majority of my fellow Americans, I ask for your support."

Simply the national audience didn't hear Nixon alone. They as well heard teams of analysts brought into the studio to dissect the speech. The retentiveness notwithstanding agitates Buchanan. "Sixty-seven percent of Americans, every bit I recall, looked to the major networks as the primary source of international and national news. 60-7 pct! And here are the guys describing what Nixon's doing, and they're all on the other side. And they're all slantin' it. Nosotros got a sense that they're continuing on our windpipe!"

The protocol was for someone on staff to call network executives and ask for better treatment. Nixon's master of staff, H. R. Haldeman, instructed Buchanan to do it. Merely he had another idea. The assistants should go public, meet the enemy—"the collective power of the national press," every bit he now puts it—caput-on. "What we had to practice was say: They are as political and ideological as we are. They've got all this ability, and there'southward a tiny handful of them, and they didn't get it democratically the style we did. And we accept a correct to fight against that power using our First Subpoena rights, just as they do."

Nixon agreed, and out of this came the most important speech communication in the modern history of the American media wars. Written by Buchanan, it was delivered ten days after Nixon'southward "silent majority" accost past Vice-President Spiro Agnew, himself a civilisation warrior itching to poke back at the liberal press, which had been ridiculing him since he was nominated. Unlike Nixon, who dismembered every draft, Agnew merely tinkered with them.

The result was a full-calibration attack on the media—on its practices and habits, the "instant analysis and querulous criticism" that came between the president and the public. Most remarkable were Buchanan's speculations on the network executives themselves, "a tiny, enclosed fraternity of privileged men elected by no one and enjoying a monopoly sanctioned and licensed by regime." What did Americans know most this coterie? "Footling other than that they reflect an urbane and assured presence seemingly well-informed on every important matter." They lived and worked in New York or Washington, D. C., Buchanan had Agnew say, where they basked "in their own provincialism, their own parochialism."

The bear on was tidal, particularly afterwards Buchanan expanded the attack, in a afterwards Agnew speech, to newspapers. The Times, for one, would later rent Buchanan's swain speechwriter, William Safire, to exist a columnist, and publish Buchanan on its new op-ed page. But the wars continued. The real trouble came, as ever, not from enemies in the press but from disgruntled administration insiders—leakers. One such, Daniel Ellsberg, handed over seven thousand pages dealing with Vietnam, the Pentagon Papers.

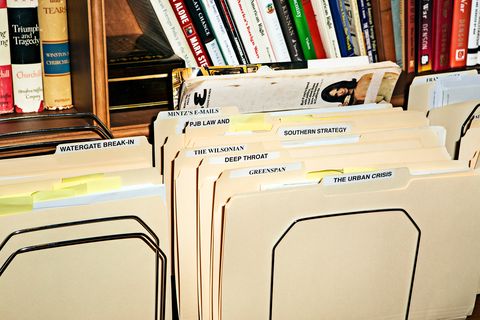

Nixon was incensed past the leak and wanted to retaliate with countersurveillance and muddied tricks. Buchanan was the first staff member approached to atomic number 82 this campaign. A gut-fighter and loyalist, he had no moral qualms and sympathized with the ambition to punish the administration'south enemies. "But in the last assay," he explained in a memo turning downwards the offer, "the permanent discrediting of all these people, while skillful for the country, would not, it seems to me, be peculiarly helpful to the President, politically." A meliorate idea, he thought, was a "major public attack" on the Brookings Establishment.

It was the wisest conclusion of Buchanan's career. The homo who took the chore instead, Egil "Bud" Krogh, appears in a group photo hanging in Buchanan's house—youngish men looking prematurely old in night suits, human foot soldiers caught in the wrong fight. Watergate felons. To Buchanan, they are comrades who took bullets for the cause. As I study the faces and signatures—Krogh, Dwight Chapin, Ed Morgan—Buchanan ticks off the jail time each received. His tone is that of a Normandy survivor back amid the white crosses of the fallen.

Nixon got millions of votes in his long career, simply he attracted few believers. Buchanan was one of those few, and he still is. His anger, all directed at the other side, is as fresh today equally it was in 1974. "If I were a special banana to the president and had taken these documents and given them to The New York Times, I would accept been fired in disgrace and charged with a crime. But if I get hush-hush documents as a announcer and I publish them, I'm a hero?"

Buchanan'southward slogan, "America First—and 2nd, and Third," coined in 1990, signaled that his was a politics of protest. And so did some other notorious eruption, his fiery oration at the Houston convention in 1992. "At that place is a religious war going on in our country for the soul of America," he alleged. "It is a cultural state of war." At the time, this sounded similar the biting cry of intolerance. And it was, with its denunciations of "homosexual rights" and "radical feminism." Only when Buchanan said that the election was "about who we are" and "what we believe," he was delivering a raw message, a shout from a distant shore, that fifty-fifty now many seem unable to hear. Our fragile moral antennae are attuned to the faintest dog whistle, merely they filter out the deeper rumbles through which democracy makes its urgent claims.

Coarseness, never the meanest political vice, matters much less than we call up. It is the lesson we learned in 2016. Buchanan has been imparting it for many years. Today, some remember the controversies over his denunciations of Israel and the Jewish entrance hall in the early 1990s. He was judged guilty of anti-Semitism by two of his heroes and allies, Buckley and Irving Kristol. Only fewer remember what prompted the dispute. Buchanan was i of a minor grouping of conservatives who opposed the first Republic of iraq invasion—the event that set the GOP on the form that ended with the election of Donald Trump.

The existent boxing, as usual, was over history. Liberals said the cold war had been about the march toward a globalized ceremonious social club. But for Buchanan and others similar him, information technology had been a state of war against godless communism. Their heroes weren't diplomats and Davos attendees. They were brutalists, like McCarthy, MacArthur, and Franco. Wills was right: Buchanan is a fanatic, though he has his own term for it. "We are conservatives of the center," he says of paleo-bourgeois America Firsters similar himself. "This is 1 reason the New World Guild, the whole idea, is gonna come down. It doesn't engage the heart. Who's gonna put on a bayonet and charge for some Brussels bureaucrat?"

Well, many of u.s. might, if the alternative is militant ethno-nationalism. But simply request the question got Buchanan exiled from his ain party. So did his criticism of foreign assist, of billions spent on defense for "rich nations that refuse to defend themselves," his scoffing at the "altruism" of the "guilt-and-pity crowd." All this while others on the Right, exhuming the earth-conquering optimism of an earlier fourth dimension, invoked a "new universalism," a "super-sovereign" banding of powers. (A confession: In 1999, The Wall Street Journal's op-ed folio commissioned me to read him out of the GOP.)

Buchanan restated his statement, courageously, in The American Bourgeois, the mag he helped found in 2002, when it was clear that George W. Bush-league was preparing the country for a 2nd Iraq invasion. Buchanan wanted no part of information technology. A war machine-history buff, he cited dark precedents: "the Ottoman, Russian, Austro-Hungarian, and German empires in Earth War I, the Japanese in World State of war 2, the French and the British the morning after." All were undone by hubris. The U. S. was next, and it wouldn't cease in Baghdad. "The neoconservatives who pino for a 'Globe War 4,' " he warned more than a decade ago, would be itching soon for "short sharp wars on Syria and Iran."

Buchanan had been expanding his case in books with grabby doomsday titles, each a renewed cry to take America back: The Great Betrayal, Country of Emergency, The Decease of the Westward, Day of Reckoning. Some verged on learned crackpottery. "Here is a difference between Patrick Buchanan and David Irving," the historian John Lukacs wrote of Churchill, Hitler, and the Unnecessary War, the revisionist history that Buchanan published in the terminal year of George Due west. Bush's presidency. Irving, the notorious Holocaust denier, "employs falsehoods; Buchanan employs half-truths. But, every bit Thomas Aquinas in one case put it, 'a one-half-truth is more than dangerous than a lie.' " The review ran in The American Conservative.

By this time, Buchanan had dropped off the grid of respectability. Running in 1996, he was compared to Huey Long and Mussolini, and the crowds at his events were likened to the goose-stepping mobs at Nuremberg rallies, presaging the epithets pinned on Trump's legions of "deplorables."

An exception, in 1992, was The Washington Post's Henry Allen, who traipsed through New Hampshire with Buchanan and found not simply race hatred but a warm nostalgia for an older time—the diner in Concord, for instance, that had a sign reading welcome dorsum to the50s along with 45 records and a encompass torn from The Sabbatum Evening Mail service. Buchanan, Allen wrote, was "paying attention" to these voters. He talked to them, and they weighed what he had to say.

Later on Buchanan lost, as he almost always did, desperately in nigh states, it all went away—the panic, the hilarity, the casual references to Nazism and fascism. He was sent dorsum to the fringes, where he belonged, a harmless creepo. At one point he joined a freemasonry of the outcast, dining one time a month at a Hunan restaurant in Alexandria with Samuel Francis and Joseph Sobran, both columnists who'd been evicted from the respectable Right—Francis from The Washington Times for espousing white nationalism, Sobran from National Review for toe-in-the-water anti-Semitism, or "counter-Semitism," equally he called information technology. Both are at present being resurrected equally forerunners of the alt-correct.

Buchanan's last hurrah in balloter politics, his 2000 entrada on the Reform ticket, resulted in a ludicrous 450,000 votes in the full general ballot, ii.4 million fewer than Ralph Nader got. But like the Confederate generals he reveres, he was defiant in retreat. "When the chickens come home to roost," he predicted to The New York Times, "this whole coalition volition be there for somebody. They're going to recall, 'What ever happened to that guy back in 2000?' At that place's no dubiety these issues tin can win."

It took sixteen years to come true, the same interval that separated Barry Goldwater'south annihilation in 1964 from Ronald Reagan'south victory in 1980. Even in the information age, movements need time. But Buchanan now has had the satisfaction of hearing his argument restated by a president, who has said, "I'm not representing the globe, I'thousand representing your land."

In this delicious moment, Buchanan has found his sweet spot. For the first time since Nixon'southward reelection, events have caught up with him. He asks Shelley to bring in a re-create of The Financial Times. The headline says, trump puts protectionism at heart of u. due south. economic policy. Buchanan chuckles. "A pocket-size victory."

There are more than these days. They arrive in the customized packages of news reports he awakens to each morn. He goes online to read Antiwar.com merely is otherwise loyal to the print journalism whose influence he helped weaken. The 5 papers he reads daily include the Times and the Post, besides as the FT. "I wasn't all that aware of Breitbart, to be honest," he says. Also, "I don't tweet."

Revolutions scramble the nowadays and cloud the time to come. But they throw new beams of clarity on the past. And the past is much on Buchanan's mind, equally his place in history grows larger and meliorate defined. He's been gathering upwardly his voluminous papers. "Shelley holds on to all my correspondence. I've got boxes of them all over the place. Three years of papers on the Nixon comeback from January 1966 to January 1969 that no one else has copies of—and eight years of papers from the Nixon, Ford, and Reagan presidencies. Also clippings, papers, speeches, memos from my three presidential runs, and xxx-five years of columns, op-eds, speech notes." He hasn't chosen an annal yet. There's still as well much to practice: proofs to correct for the new Nixon book, a promotional tour to complete.

Suddenly, what Pat Buchanan thinks matters to just nearly anybody, NPR and Politico as well equally Fox News. He has a good bargain to say, but then he always did. The volume that got him fired from MSNBC, Suicide of a Superpower, isn't but a litany of provocations. It is a alarm that the country is changing. "A rebellion is nether way in America," Buchanan wrote in 2011, "a radicalization of the working and middle class . . . a populist rage against a reigning establishment. But what explains the failure of the establishment to understand its countrymen?" Today, many others are asking this, besides.

The last joke is that Buchanan knows besides as anyone that the good one-time times aren't coming back. "I get my Un statistics, and the latest ones came in on these big wall charts," he says. The writing, so to speak, is on the wall. Item: "Africa has 1.1 billion people. Will accept 2 billion in 2050, and 4 billion in 2100." Detail: "There's not a single state in Europe, salve maybe Iceland, that will have a birthrate to enable its native born to survive and endure as the majority in those countries at the end of the century." And America? "Texas, California, Hawaii, New Mexico," he notes, are already majority nonwhite.

Merely look at the seat of the Republic. "Trump got four per centum of the vote in my hometown—4 percent! A Bolshevik would have done better than that when I was growing up!" Another burst of laughter. "I couldn't believe it. California'southward a state Richard Nixon won 6 times. The first time he went for the Senate, he set a state tape. 1950. He won it six times, lost it for governor once. Reagan won it in iv straight landslides." Today, there is talk that California volition secede from Trump's America, from Buchanan's. "Some of us," he says, "are for it."

And what of Trump's early days in office?

"I'm very hopeful some of the things can be done, but I'one thousand pessimistic nearly whether we can plow it around," he says. For one matter, Trump'southward reluctance to admit fault is worrisome. "White Houses arrive trouble when they don't tell the truth about blunders and mistakes," Buchanan wrote in an electronic mail. And while it's paramount for presidents to stay on good terms with Congress—"a loyal majority is indispensable to become things done, and to encompass your back"—Buchanan warned that Trump's wellness-intendance pecker would leave "millions of working-class folks who placed their trust in him out in the cold." The silent majority knows what betrayal looks like, and if it happens again, Pat Buchanan will be there, ready to get 1 more round.

This commodity has been updated to include Garry Wills's recollection about the origin of his 1968 Richard Nixon profile.

This content is created and maintained by a 3rd party, and imported onto this page to assist users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io

Source: https://www.esquire.com/news-politics/a54275/charge-of-the-right-brigade/

0 Response to "Make Britain Great Again Invades Communist Bookstore"

Post a Comment